Martial vs Art: Chapter 1, Part 2: Myth Busting 101

Continuing the Martial vs Art series with Chapter 1, Part 2: Myth Busting 101

Martial vs. Art: The Duality of Martial Arts History and Debunking its Moral Superiority:

Around The World

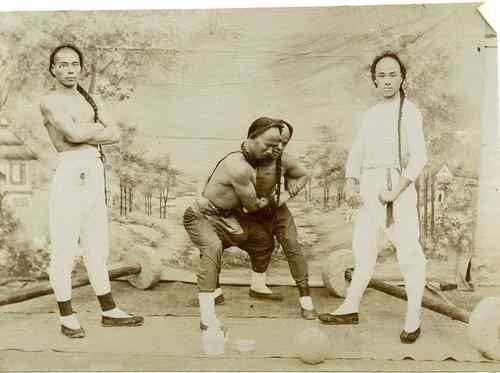

Another narrative piece we have to smash, and one of the most significant ones about martial arts: the synonymous association between Asia and martial arts practice.

Like the narrative with Wrestling, this is a complete misrepresentation and plays into larger issues present in the idea that martial arts are developed in a sphere of ethics, morality, and self-cultivation.

While Europe’s martial arts have declined to near obscurity, it does not mean that those arts did not exist or were not significant to Western culture.

Other regions of the world, such as Africa, South America, or the Southern Pacific, had robust systems of combat as well, but are rarely, if ever, mentioned in larger conversations about martial arts.

“All cultures have martial arts; highly developed fighting techniques are not unique to East Asia. It is merely a modern construction that consigns boxing and wrestling, for example, to the realm of sports (and Olympic competition) and extremely similar East Asian fighting techniques to acceptable activities for middle-class Westerners. Even fencing, shooting, and archery qualify as sports, albeit not very popular ones, while East Asian forms of fencing, archery, or other weapon use are martial arts.”

Today, the term ‘martial art’ is typically synonymous with ‘Asian fighting art,’ associated with styles, systems, and techniques mainly from China, Korea, Japan, and Thailand, with other regional neighbors such as the Philippines, Burma, Indonesia, India, and Vietnam in a secondary sense.

The standard view is that the West's only contributions to martial arts are restricted to Boxing, Savate, Greco-Roman Wrestling, and Fencing, if they even get that. While it could be said that Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and Mixed Martial Arts hold odd middleman positions between East and West.

While systems like Catch-As-Catch-Can or Luta Livre remain niche outside of small circles, but are some of the most influential Western systems of the past century. Even if they lack mainstream acknowledgments.

On the continent of Africa, distinct arts can be found throughout the region, much of which evolved and developed in isolation from other African arts to produce practices unique to both area and culture.

Several armed combat systems were developed among the Zulu people of Southern Africa, involving a trifecta of club, spear, and shield that covered all necessary combat ranges. This combination of club and shield was used similarly to the European sword and shield.

A wrist bracelet known as the bagussa was used as a self-defense weapon, incorporating sharp edges, and was common among the Nilotic people of the southern Sahara region in Africa, including Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia, against slavers.

Even today, it’s used by Turkana women of Nigeria for self-defense purposes.

Alongside weaponry, unarmed combat systems can be found throughout Africa as well. The most well-known of these are long-standing wrestling traditions, the kind seen in Egyptian etchings or paintings of Sudanese Nuba wrestlers.

The most well-known of these systems is Senegalese Laamb, a wrestling style closely resembling Greco-Roman.

There’s also the Khoikhoi of southwest Africa, an unarmed wrestling system resembling Pankration. And Brazilian dance-fighting art of Capoeira has its roots in Africa as well, with its earliest form holding the customary title of Capoeira Angola, connected to the men of Southern Angola.

Similar examples can be found across the Caribbean, including Mani in Cuba, Chat'ou in Guadeloupe, and Susa in Surinam.

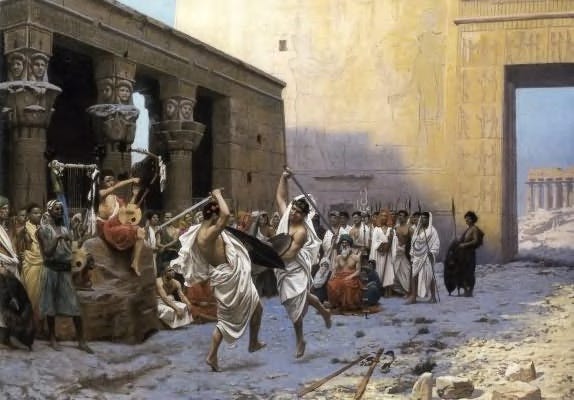

One of the most distinct aspects of African martial arts is the integration of dance and rhythm for training and practice.

"One of the more interesting features of African combat systems was the reliance in many systems on the rehearsal of combat movements through dances. Prearranged combat sequences are well-known in various martial arts around the world, the most common examples being the kata of Japanese and Okinawan Karate...Warriors either individually or in groups, practiced using weapons, both for attacking defensive movements, in conjunction with rhythm from percussion instruments. The armies of Angolan queen Nzinga Mbande, for example, trained in their combat techniques through dance accompanied by traditional percussion instruments."

In ancient Greece, similar examples can also be found in Pyrrhic war dances and Chinese Kung Fu's endless list of unique family systems, animal-inspired, or combat-centric forms.

Moving from Africa to Europe, for centuries, highly sophisticated and codified European martial systems existed and thrived, with evidence suggesting combat arts can be found as far back as 5,000 years.

It is actually from Latin, where the English term ‘martial arts’ derives from and means ‘arts of Mars’ or arts of 'the Roman god of war.'

"The term "martial art" was used in regard to fighting skills as early as the 1550s and an English fencing manual of 1639 referred specifically to the science and art of swordplay. In reference to Medieval and Renaissance combat systems the terms "fencing" and "martial arts" should thus be viewed as synonymous. Fencing was in essence the "exercise of arms" - and arms meant more than just using a sword. Prior to the advent in the mid 1500s of specific civilian weapons for urban dueling, the use of personal fighting skills in Western Europe were primarily for military purposes rather than private self-defense, and fencing was therefore by definition a martial (i.e., military) art. The study of arms in the Middle Ages and Renaissance was for the large part not exclusively fixed upon either judicial combat or the duel of honor, or even on the knightly chivalric tournament. Yet neither was it intended for battlefield use alone."

Other examples of European combat systems can be found on the Italian peninsula, whose long history dates back to Rome, where:

"Romans of all classes were also adept at knife fighting, both for personal safety and as a badge of honor. Intriguing hints of gladiator training with blunt or wooden weapons and of their combat with animals suggest a complex repertoire of combat techniques. Speculation exists that some elements of such methods are reflected in the surviving manuals of medieval Italian Masters of Defense."

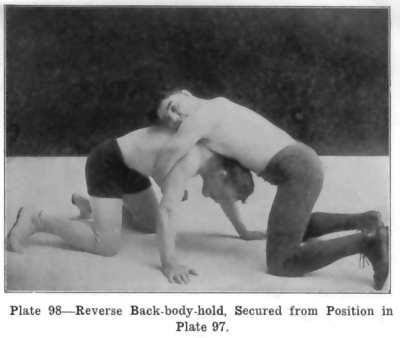

After the fall of Rome, Celtic tribes carried on rich combat training traditions, eventually leading to medieval warrior culture. Unarmed techniques were included in a German text called the Kunst des Fechtens (art of fighting), which taught a wrestling and ground fighting system known as Unterhalten (holding down) and the typical German Fechmeister (fight-master), "was well versed in close quarters takedowns and grappling moves that made up what they called Ringen am Schwert (wrestling at the sword)."

In 1509, a Spanish master at arms, Pietro Monte, published the Collecteanea, a manual on the art of knighthood, martial arts, military practice, and other related practices published in the early 1500s.

In 1659, the techniques of Johanne Georg Paschen included complex and sophisticated unarmed defense illustrations such as boxing jabs, finger thrusts to the face, low-line kicks, and a variety of wrist and arm locks.

In Russia, at the beginning of the reign of Peter the Great in 1682, it is said that Russian peasants were so proficient at stick fighting that one of Peter's first official acts was to stop it.

The rapier rose from:

A “practical street-fighting tool to the instrument of a ‘gentleman's’ martial art in Western and Central Europe from roughly 1500 to 1700. No equivalent to this unique weapon form and its sophisticated manner of use is found in Asian societies, and no better example of a distinctly Western martial art can be seen."

All of this is not even to mention the existence of Irish, Scottish, Welsh, and Cornish wrestling traditions or the wrestling arts of Glima in Iceland, Schwingen of Switzerland, or Yagli in Turkey.

And that is barely scratching the surface of European martial arts tradition.

Unfortunately, exploring European martial arts history and how they've been lost to time and the overall martial arts zeitgeist is another deep dive that - while immensely interesting - is something that cannot be covered in full in this series.

For brevity’s sake:

"Despite gaps in the historical record, it is apparent that for better than two millennia unarmed combat was developed, refined, and practiced by cultures as empires rose and fell. Armed combat shifted and changed with the advent of new and improved military technology. Clearly, fighting systems that required sophisticated training and practice have been in use in the "Western" regions of the globe as long as many Asian martial arts." Thanks to the advent of firearms, this drastic change of warfare discouraged many hand-held weapons and close-range combat systems for obvious reasons. As military technology and societies changed, the West's indigenous martial arts were, in turn, relegated to sport and pastime or just vanished altogether. "Sport boxing, wrestling, and sport fencing are the very blunt and shallow tip of a deep history that, when explored and developed properly, provides a link to traditions that are as rich and complex as any to emerge from Asia."

Christoph Amberger, in The Secret History of the Sword: Adventures in Ancient Martial Arts, adds:

"The absence of ancient European martial arts from the collective memory of the 20th century can be attributed to several factors. First and foremost, their mostly oral mode of transmission (and the secrecy in which some systems were practiced and taught) made sure all traces were lost once the last masters had died. And even those masters or systems that left literary sources were at the mercy of academic philistines unable to interpret references outside of the context of their disciplines."

Then v. Now

The modern martial artist at the start of the new millennium, 2000 CE, and the years forward can generally be categorized as falling into one of three buckets:

A 'mixed martial artist,' a 'traditional martial artist,' or a crossover between the two.

Regardless of the label, these practitioners train hand-to-hand.

As a sport-focused art, there is no emphasis on weaponry for the mixed martial artist and little focus on weaponry, if any, for the traditional martial artist, as their practices remain mostly a formwork-based skill.

Outside of specialized practices such as Kendo, Kali, Fencing, or Historical European Martial Arts, weaponry is limited and minimized compared to the practitioners of antiquity, holding no actual need or genuine priority.

Even within self-defense-related philosophies or specialized practices like Kendo, the formwork of weapons training is only used to sustain tradition or compete in a sport with no practical value.

I'm sure there are readers seething over this idea, but walking around with a Katana or Longsword isn’t just frowned upon in many places.

It’s outright illegal.

The basic fact is that actual weapon use is not an option for self-defense.

And in an age of firearms, who wants to bring a sword to a gunfight anyway?

Essentially, participation in any martial art in a modern context is voluntary, whether the pursuit is based on competition, recreation, self-defense, or health. In rare cases, it might be tied to military service--but there’s no real comparison between modern military combatives and ancient practices outside of the most loosely implied generalizations of being 'in the military' and 'practicing martial arts as part of training.'

To shave that all down to a fine point, modern martial arts, when compared to historical counterparts, are not that distinctly different from one another outside of movement and how that movement is applied or practiced.

Basically, what is the rule set, and what is legal and what is not?

And, this style defends a jab this way; this style attacks with this ligament compared to this one (excepting, of course, the occasional chi blasting, 30th-level guru, which is a world unto its own), or we prefer punching to strangles.

Comparisons of the modern situation to the martial artists of the late 1800s show that the past contained a much more considerable contrast to what a martial artist entailed.

For example, rather than something voluntary or positive, martial arts were marginal, often seen as culturally backward, and outright banned in some places. In other parts of the world, martial arts were a revolutionary stance of tradition versus Western imperialism and modernization.

Or, outside of Asia, Savate and the ‘Marquess of Queensberry rules’ were taking on quite a different shape in France and Britain from those of their Eastern counterparts.

And that’s just a high-level overview.

When you get into the weeds, every methodology or ‘martial art’ held a distinction in both its practice and place in society, with an impossible list of variations and unique circumstances during their respective eras.

Here are a few select examples and summarizations that will help better grasp the gap between the different forms of martial arts development in this era.

In the 1800s, Japan's most traditional martial arts practices were dying off due to the modernization efforts of the government, cultural elements of Western influence, and a general societal desire to move past feudal-based practices.

However, thanks entirely to the efforts of Jigaro Kano and those studying at the Kodokan, these arts survived.

In Kano's efforts to turn traditional Japanese Jiu-Jitsu systems rooted in warfare into the more streamlined Judo practice, he modernized what many Japanese felt belonged in the backward past and no longer had a place in society.

In China, martial arts faced a similar situation, with a battle between tradition and modernization.

Yet, Chinese martial artists were not modernizing in the same fashion as Japan, where they were slowly shifting from war to sport (not addressing the militarization of Japan in the early and mid-1900s).

Chinese martial artists were, instead, directly influencing and participating in a series of civil upheavals--from the Taiping Rebellion to the Boxing Uprising. Under the Qing Dynasty, martial arts or being a ‘martial artist’ were usually seen as being anti-Manchu, the ruling government at the time. The state associated martial arts with rebellion.

In many instances, it was either suppressed and controlled or outright sought out and eliminated through purges, with martial artists at the forefront of revolutions and civil conflicts.

In France, Savate was in a different situation:

"The earliest known reference to savate is found in Mémoires de Vidocq (1828); here, the word referred to a combat sport, and also to bare-fisted duels. The savate and chausson were ways to solve the problem of settling disputes of honor between rough, tough men at a time when using weapons was forbidden...During the first half of the nineteenth century, savate and chausson were taught in the street, the cellars or the back rooms of cafés. Théophile Gautier thought savate should be taught at school: he suggested replacing the word savate, which had vulgar connotations, with that of "French Boxing" which was a synthesis of savate and chausson. By the mid-1800s, the discipline was well established and had several styles. One style appeared in music halls, where acrobats such as Rambaud (alias la Résistance) and Louis Vigneron gave spectacular shows, kicking while doing cartwheels, and punching in mid-air while jumping. Such extraordinary moves astonished spectators. Another was the self-defence model, stemming directly from the original practice, which was used by Michel Casseux (alias Pisseux) and others. Finally, the gymnastic style developed by the Lecour brothers became common during the 1860s. During the mid-nineteenth century, French Boxing was advertised as a serious discipline. The rigorous physical training resulted in good health, and the programs were advertised in a way that had appeal to a bourgeois and comparatively wealthy public."

Still exploring the regional implications of the martial arts of the 1800s worldwide, in South America, Capoeira was engaging in its own fight with an indigenous population rejecting its colonial rulers, in this case, the Portuguese.

"The practice [Capoeira] in itself was considered 'unacceptable', requiring immediate 'correction' and subsequent punishments, officers did not need to write detailed reports about arrested capoeiras...From 288 slaves that entered the Calabouço jail during the year 1857– 1858, 80 (31 per cent) were arrested for that reason, and only 28 (10.7 per cent) for running away. 40 Out of 4,303 arrests in Rio police jail in 1862, 404 detainees— nearly 10 percent— had been arrested for capoeira. What treatment awaited detained capoeiras? As we have seen, immediate 'correction' was initially administered in the form of whipping. During the first years of repression, capoeiras were given between 100 and 300 lashes in jail and then released. In 1824, the government substituted the whipping of capoeiras by three months' work in the navy dockyards."

That’s the difference between martial arts in four countries, during the relatively same time period.

Quite a bit of difference.

Continuing to try to better understand our modern view of martial arts versus that of the past, contemporary combat training carries connotations of unarmed combat. In the past, however, a martial artist would have trained in weapons, such as swords, spears, or archery, as their primary focus of training, rather than the minimal amount mentioned today.

Unarmed training was the secondary backup tool for battle and was usually used for building discipline over any core combat instruction.

"In real combat, bare-handed fighting was not as useful as the staff that the [Shaolin] monks had been practicing for centuries, not nearly as lethal as swords and spears that they had always employed in battle, and certainly not as dangerous as firearms that, having been invented in China several centuries earlier, were being reintroduced to it by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century."

To hammer home a little more the lack of effectiveness that hand-to-hand combat holds in actual battle when one is faced with weapons or better options, the Greek playwright Euripides puts it as bluntly as one could:

"What outstanding wrestler, what swift-footed man, or discus hurler, or expert at punching the jaw has done his ancestral homeland a service by winning a crown? Do they fight with enemies holding discuses in their hands or by kicking through shields with their feet expel the country's enemies? No one standing next to steel indulges in this stupidity."

As members of modernity, we also need to take our future-person glasses off and understand how we view our world and how our experiences, perspectives, morality, and philosophies are not exactly shared with our ancestors.

References:

Taylor, K. (n.d.). Kronos: A Chronological History of the Martial Arts and Combative Sports 0000-0499 . Electronic Journals of Martial Arts and Sciences. Retrieved September 26, 2021, from https://ejmas.com/kronos/NewHist0000-0499.htm.

Lorge, P. A. (2012). Chinese martial arts : from antiquity to the twenty-first century. Cambridge University Press.

wushutigeriron. (2021, August 7). The hidden history of Shuai Jiao - part one - kungfu explained #06. YouTube. Retrieved October 9, 2021

Poliakoff, M. B. (1995). Combat sports in the ancient world: Competition, violence and culture. Yale University Press

Shahar, M. (2008). The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

Kagan, D. (2016). Men of bronze: Hoplite warfare in ancient Greece.

Polybius, Scott-Kilvert, I., & Walbank, F. W. (2003). The rise of the Roman Empire. Penguin.

Cole, M. (2018). Legion versus phalanx: The epic struggle for infantry supremacy in the ancient world. Osprey Publishing.

Green, T. A. (2001). Martial arts of the world: an encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO

Clements, John (January 2006). "A Short Introduction to Historical European Martial Arts" (PDF). Meibukan Magazine (Special Edition No. 1): 2–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012

Loudcher, Jean-François. (2008). History of savate.

Assunção, Matthias Röhrig. Capoeira: The History of an Afro-Brazilian Martial Art, Taylor & Francis Group, 2002

Euripides, Autolykos fr. 282 N., cf Juthner-Brein, I.95