Martial vs. Art: The Duality of Martial Arts History and Debunking its Moral Superiority

Part 1 of my ongoing series Martial vs. Art: The Duality of Martial Arts History and Debunking its Moral Superiority

Edits by

Introduction

I am what one would call a 'big ol' geek.'

My first experience with martial arts was the same for many children who grew up in the ’90s, beginning with Mighty Morphin Power Rangers and then Dragon Ball Z, which only solidified my love of all things ‘fighting’ not long after. I was enrolled at a local Okinawa Kenpo Karate school around age 5, which parent you ask will determine whose idea it was to get me into my martial arts. From that point forward, in some way or another, combat arts have always been a part of my life— at times, as a passion that encapsulated my very soul and being, and at the very least, remaining as a routine hobby, to most currently, a fully formed business venture.

It’s always been there and seemingly always will be.

Around 11, I switched from Karate to Aikido; it didn’t last long. I wanted to learn something more applicable, something more real, a style that didn't attach my belt promotions to knowing the exact Japanese names of every technique.

I just wanted to know how to "fight good" in so many words. At 13 I was faced with a choice: did I want to try Kung Fu or learn Jiu-Jitsu?

I had recently been binge-watching the first couple of Ulitmate Fighter seasons from Blockbuster, which my Dad had rented out of his own interest—knowing I'd probably like them too. I was already over Aikido and wanted to keep moving forward on my journey to 'mixing the martial arts.' My Dad knew a local Jiu-Jitsu school not too far from our home. But, he also knew a much closer Kung Fu school within walking distance of our house, that a few of the town's police officers took lessons at.

Looking back, I should have chosen Jiu-Jitsu from an application standpoint, but two things happened.

One, the school was literally less than a ten-minute walking distance from my house, only a few if you drove, and two, the Bourne Identity had been recently released, and the Kung Fu instructor did a really cool self-defense sequence with a pen. I loved Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung, and all things Shaw Brothers, plus martial arts started in Shaolin, right? Who wouldn’t want to take part in that kind of legacy?

I was sold. I chose the Kung Fu pill.

However, while my roots started in traditional martial arts, it didn't take long to transition into "MMA." After those first UFCs from Blockbuster, I started renting later events with the obvious household names at the time, Chuck Liddell, Randy Couture, and Tito Ortiz. But, I didn't limit myself to only the UFC; I'd find PRIDE highlights or fights in the early Wild Wild West days of ‘limited’; by limited, I mean nearly non-existent copy-right infractions on YouTube and Daily Motion.

I had been doing martial arts all my life, and while I wasn't much of an athlete, I couldn't help but not want this to be my life.

Even as I was still training in Kung Fu, I began dipping my toes into even wider martial arts pursuits.

I tried wrestling in High School, and around 18, I found a local MMA gym called Liberty Boxing— where I joined knowing if I was going to compete against ‘BJJ’ and Muay Thai fighters as a ‘Kung Fu guy,’ I should start learning what the 'opposition' was doing.

I will always distinctly remember when a training partner at my Kung Fu Academy jumped into the amateur MMA circuits, the “Your Kung Fu is No Good Here” t-shirts in abundance around the Atlantic City promotions, which are almost all now defunct.

And yet, when I joined Liberty, I still didn't learn Jiu-Jitsu, at least not Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. The coach at the gym I had signed up for was a Judo blackbelt from Nigeria, who had moved to Germany and then the United States and very adamantly did not teach 'BJJ.’ Just Judo without the gi and a heavy influence on Newaza, as the owners wanted to capture that sweet, sweet grappling marketing.

Then there was the striking coach, an old-school Joe Lewis affiliate and Kickboxing instructor, not the cookie-cutter 'Muay Thai' teacher a young student might expect to find at the time.

Both men were excellent instructors and competitors in their own right. Even now both are over 50 and shredded like anime characters. These men are also the only select individuals I respectfully address as Sensei.

Unfortunately, Liberty Boxing flamed out quickly due to a few very poor financial choices and bad business practices by the owners. They actually had a few of us packing up the gym in what they called a "move to a bigger location across the street," only to find out there was no actual move. They were closing. If I hadn't been helping move equipment that day, I wouldn't have even known they were closing up shop. They told no one, even instructors and coaches, and were still billing and even double-billing after the fact.

Irrelevant noise to the story.

At the time, I was supposed to have two amateur MMA fights under this gym, which did not pan out considering the circumstances.

Interestingly, this same gym, for its short period of existence, would also be the 'martial art' starts of two very prominent careers, Daria Beranto, now known as WWE's Sonya Deville, and the 'Black Belt Slayer' Nicky 'Rod' Rodriquez.

With my gym closed and continuing some Kung Fu private lessons, I then went on to join another local gym, Nextgen MMA. The head instructor was pretty successful around the NAGA and Grappler's Quest circuit, with a curriculum more traditional to the 'MMA' landscape: BJJ, Muay Thai, and Wrestling.

I was back on track and on the path of eventually getting that first amateur bout…and then I herniated a few disks in my back and dislocated my ankle, among other associated injuries.

I was still training with my old Judo instructor at the time. He had started teaching in Delaware temporarily, and I would travel from New Jersey across the bridge to learn until he opened his own facility back in N.J.

Unluckily, after working a manual labor job that summer and putting more wear and tear on a back that had been genetically predisposed to sucking (bad backs are the mark of a true ‘Massari’), plus the poor lifting forms associated with newbs and heavy weights, one well-defended Tai Otoshi was the straw that busted my back. I still occasionally put my back out from Tai Otoshis, Harai Goshis, and Uchi Matas to this day.

There is just something about twisting your body and wrenching a resisting human body that always seems to do it. Who’d have thought?

Around the time I joined Liberty Boxing, I had also started college at Rowan University. For me, college was about going 'cause you're supposed to' and using it as a backup plan if fighting didn't work out. My mindset was that college would be pointless because I would break Georges St. Pierre's record as the youngest UFC champion (this was, of course, before Jon Jones broke that record).

Retrospectively, the backup plan was good to have.

During my first few semesters of school, I was enrolled as a double major in History and Philosophy & Religious Studies. The fallback for my soon-to-be great martial arts career was to become a high school history teacher, thanks to how much I had liked one of my own. The focus of my Religious Studies degree was Eastern religion, along with a minor in Philosophy as an added nerd bonus. Eventually, as priorities changed, maturity set in, and the fact that life never quite pans out exactly as expected, a tiny internal seed that had always been sitting in my subconscious began making itself known.

Since the condition of my back made training basically non-existent, I found myself interested in pursuing other, less physically strenuous goals. It was something that I had even planned on using my MMA career to help pivot me to later in life (when that was still my option A): professional writing.

For years, running alongside my desire to fight was a desire to write, specifically comics and nonfiction history. I was hardcore into MMA; I'm talking all-nighters streaming DREAM fights and, as a Jersey boy, knowing the 'glory' that was YAMMA. It was only sensible as a young man in the heyday of Sherdog or Bullshido forums to want to turn his (always without a doubt, absolutely and unequivocally correct) MMA analysis into something long-form.

I was a Cage Potato and Middle Easy diehard. Middle Easy specifically influenced every aspect of my early writing style; dropping 'rawesomes' whenever I could, sprinkling in pop culture deep cuts, and adding a love for Wu-Tang that dropped ‘Hip Hop Head’ neatly into my geekdom list.

I began publishing to Bleacher Report when they used to let anyone make posts. I got in touch with an MMA and Pro Wrestling blog, Hit The Ropes, through a high school acquaintance and began regularly writing for them—even getting to do on-air interviews with Anthony McKee and Kim Couture (the latter of whom was less than thrilled by some of my questions). I also got to do some local, “on location” interviews with Nick Catone and his instructor at the time, Bill Scott. Scott had even set up a time to do an interview after his own, with a young Frankie Edgar and Kurt Pelligrino, but thanks to a dead camera battery and a mishap with spares, what could have been never was.

These days made me realize, ‘Hey, writing can be a career.’ I'd always wanted to write but felt like there was some secret formula I needed to make it happen, believing if I made it in MMA, it would create marketability to achieve my true dream and passion. Something akin to my favorite fighter at the time, Jason ‘Mayhem’ Miller, and Bully Beatdown. At various points, I was even rocking my own Strip of Doom knockoff, the ‘Strip of Rawesome.’

So, I dropped the history major and decided to switch to journalism, still doubling up with Philosophy and Religion, and as they say, the rest is history.

Eventually, thanks almost in totality to my martial arts background and less about my degrees, I was able to land a job with a martial arts company running social media accounts for their clients, which were academy owners of all kinds. This was a nice change of pace from my currency position at the time, working the surprisingly eventful midnight shift as security in Camden, NJ.

Eventually, I packed up and moved from N.J. to Washington, D.C., to be closer to my new form of martial arts-related employment.

The main company was an older billing service, which exclusively worked with martial arts schools, and had begun to dabble in other offerings for their clients. The model for my position was that instructors are incredibly busy running their schools and don't have time to dedicate to social media accounts to bring in new students or do basic marketing, so I did it for them. I was later promoted to the Lead Social Content position and again, to Content Manager for another one of their subsidiaries—which was more focused on business education, content, and aspects larger than just social media.

It was by far the most fulfilling job I've ever had, working with martial arts instructors and getting the opportunity to interact with the community daily.

Over the course of two short years through that position, I had the chance to build personal connections, interview, shoot video content, travel, and (as a side bonus) train with everyone from Steven ‘Wonderboy' Thompson, Tom DeBlass, Jason David Frank, Kayla Harris, Travis Stephens, Jesse Enkamp, Jimmy Pedro, Bill ‘Superfoot’ Wallace, Josh Barnett, the Valente Brothers, Erik Paulson, Ricardo Almeida, and so many other amazing martial artists at every level. I even got a feature in Black Belt Magazine after connecting with one of their editors at the Martial Arts Supershow. Something that would have ever occurred had I not been on location to promote my employer’s business.

Of course, during all this time, I never stopped training either.

Priorities and goals might have changed, but the martial arts never did. During college, I did an internship in New York City with Heavy.com, due to their MMA presence, but they had then shifted away from anything that wasn’t news coverage. I stayed with my aunt and uncle, taking the train back and forth from NJ to NYC. Back in New Jersey, I enrolled in Ricardo Almeida’s academy, which was near where I was staying. While our only interaction at this time was one passing ‘hi’ in a hallway, I trained there until the internship was over and would later get to meet Ricardo more personally after I graduated and started my real ‘big kid’ job.

After graduating college, I trained at a local BJJ Academy a friend recommended for a short time and did Kung Fu privates as often as I could, before moving to D.C. That move gave me the chance to train with TUF Season 22 Winner and ADCC Bronze medalist Ryan Hall, and LFA and ONE Featherweight Championship, another TUF alumn, Thanh Le, at Ryan's 50/50 Academy in Falls Church, VA. Still to this day, 50/50 has been one of the most illuminating and enlightening experiences I've had about the martial arts thanks to all of the fantastic coaches and students who walked through those doors; everyone from D-1 Wrestling studs to IBJJF and ADCC veterans, UFC veterans, top-level Judoka, the talent that walked through those doors on a random Friday night could not possibly be overstated.

After enlisting in the Air Force, I found myself in Biloxi, MS, for technical training, where I would visit Alan Belcher's gym on weekends when I could find the time. In the process suffering injuries in both of my ankles, ligament issues, arthritis, dislocations—all thanks to gambling with the devil in leg lock battles that did not go my way. These days, back in NJ, I train under UFC Veteran and former CFFC champion, Jonavin Webb, and once again with my former Kickboxing instructor, Phil Maldonato. I couldn’t be more privileged to share the mats with so many UFC, CFCC, IBJJF, and ADCC veterans and up-and-coming competitors and martial artists. Humbled by those light years ahead of me on a daily basis.

It’s through this long history that I feel my background in martial arts gives me a unique perspective, along with specific insights that aren't those of a typical traditionalist or 'mixed martial artist.'

Having started in traditional styles before moving into 'MMA' has left me uniquely well suited to critique traditional techniques' dogmatic adherence to 'old ways' and superstition, as well as an inability to evolve. Especially given the lack of live training, sparring, or real drilling that leads to any legitimate martial skill.

I can also point out the, *gasp*, shortcomings in MMA, which all too often approaches the martial arts in a generic, one-size-fits-all framework; meat and potatoes training of Muay Thai, Boxing, Wrestling, and Jiu-Jitsu in an assembly line process with no real 'art' to speak of.

The individuals at the highest competitive level in martial arts are not products of this cookie-cutter training.

The average semi-mixed martial artist, however, generally looks no different from the lower-level professional. It isn't until fighters reach the higher echelons of the game that we see the 'art' in the martial arts that takes shape and the fight metas that they’ve built to succeed at the top of the sport.

My education, as mentioned earlier, has left me reasonably well versed in philosophy (I have a neat piece of paper that says so on the subject, at least) and the ease at which philosophical principles of Daoism and Zen Buddhism can be applied to physical combat techniques has made a significant impact on me over the course of my life. I even partly based my senior thesis on Daoism and martial arts.

Again, I am a 'big ole geek,' and spent plenty of my free time reading On The Warrior's Path (thanks

), the Bubishi, Striking Thoughts, Book of Five Rings; more martial arts books with philosophical undertones than I can remember, all of which have had their own unique impacts on my perception of the subject.I wholeheartedly believe there is a connection between philosophy and martial arts. In many ways, martial arts are the physical manifestation of philosophy.

But, I've also learned what really good marketing and a few glasses of Kool-Aid can do, especially in martial arts. There is a duality, with the ideological battle between 'traditionalists' and 'modernists’ having resonance in older themes than most realize.

While the roles and topics have shifted, the ideas themselves haven't.

Many more have tried to use the martial arts as some unique morality and ethical builder for longer than most realize, hoping to build distinctions between this noble craft and savage, unschooled fighters.

The fact is that martial arts have never genuinely been about respect or morality. They have been about war, violence, combat, entertainment, and imposing one's will over another. Self-mastery and becoming a better person isn't the principal consequence of this trade. It's a nice afterthought to a predominantly ‘rough,’ even mindless, practice.

It's time to dispel the idea of the martial arts' purity,' embrace its less virtuous history, and break the myth of its nobility. The martial arts are just as messy, unappealing, and raw as they are beautiful, philosophical, mentally engaging, and self-developing.

To find value in ‘both,’ it’s my goal to shed light on the darker side that tends to get less ‘shine,’ as the youths say.

I hope to explore the whole picture of martial arts and what history actually tells us —that every martial artist who has dedicated their life to improving themselves is also entwined in a collective narrative that includes individuals who use their skills simply for violent acts.

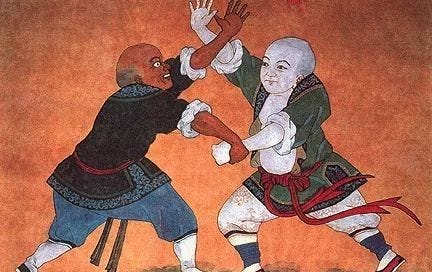

We must stretch back to the earliest days of combat sports, in Pancrase and Gladiatorial matches of ancient the Mediterranean; the pugilistic roots of the United Kingdom that led to modern boxing; “worked" fights from Chinese Shuai Jiao to Lucha Livre to American Catch Wrestling all the way through to modern Professional Wrestling. The latter of which, I might add, has opened more doors for other combat sports as forms of entertainment than I think martial artists are comfortable acknowledging.

And, of course, the development of martial arts in America, Brazil, Japan, and China, often forged and grown through 'dojo storming' and the destruction of other schools.

Gordon Ryan, one of the most prolific and accomplished No-Gi grapplers of all time, summed up the 'other side of martial arts in all the crude glory I hope to present.

"I love how people say 'BJJ is built around respect and honor.'" Ryan wrote in a 2018 Instagram post. "No, it's not! It is built around savage Brazilians kicking the shit out of people just because they could. Storming gyms of other martial arts and fighting their instructors just to show how superior BJJ was. And while I think that is fucking awesome. It's not the fairy tale you guys tell about respect and honor. This sport is built around real men who did give a fuck took what they wanted."

Dave Leduc, a Leithwei champion and the first non-Burmese to win a Lethwei Golden Belt, echoed those sentiments.

"I don't get all the disrespect on muay Thai and shit," he wrote, in reaction to a fan on social media, "isn't martial arts meant [to] be about respect an all that good stuff?"

"No, it's not," Leduc posted in response to his own question. "Look at BJJ. It was a bunch of Brazilians who stormed martial schools, called out the teachers, and fucked them up, to show which Martial art is better. That's the origin. You can live in lalaland all you want, but it's always been about showing dominance, inflicting pain and even killing back in the day. Sure, it's cool nowadays after a fight, that we show respect to each other for the war that we just fought, it feels good, but it's never been about that. It's about killing people. I respect my people, my coaches, my teammates, that's it. I might respect my opponent at the end if I feel like it."

"The definition of "Martial" means 𝗪𝗮𝗿. The Martial law is declared in times of war, and in war you don't give each other hugs and bow. You do so preparing for war with your mentor, but to your opponent, there's no mercy."

Like any history, these 'renegade' individuals do not need our reverence or fetishization. We don’t have to consider them heroes. However, this aspect of martial arts needs acknowledgment; it’s important people understand the impact, that the martial arts are not some unique religious experience that absolves all ‘sinful acts.’

Violence, chaos, and a desire to cause harm are not outliers or irregularities in the long history of the martial arts.

Hopefully, along the way, we’ll uncover the Yin and the Yang of this pursuit. Allowing us to achieve a complete picture of reality, history, and what makes the martial arts such a fascinating subject to study.

In order to shed our preconceptions and take an eye-opening look at the martial arts in all of its raw and violent glory I want to establish some ground rules about what to expect on the journey forward.

First is the history; as much as I'd like to write a book on the history of martial arts, or even the history of specific regions or styles, that’s outside the scope of what I'm looking to accomplish here.

This means I will have to gloss over, leave unmentioned, summarize, and largely avoid deep dives unless absolutely necessary. There will be points where the history might get dense, but the purpose will always be first and foremost to provide context and evidence for the larger thesis.

Next, and this will come up ad nauseam, is language and definitions: it might not seem very important, but it is, especially when translating ideas across space, time, and culture.

What is a martial art? Is a martial art from 2020 BCE the same as a martial artist in 2020 CE? Where is the overlap, and where are the differences? Does the term mean the same in different circumstances? Does martial art mean the same in South America as in Northern Europe, the Middle East, or West Africa?

These are a few of the basic questions that we will have to address. I will constantly layout prefixes of language and definitional perimeters but stick with me because it's only setting a framework. At a certain point, it will not need to be addressed as often once presented.

Last is the path from start to finish, aiming to shatter the myth of martial arts "ethics" and that its practice does not inherently imply a better morality or ethos. To do so, there is a good deal of material to cover and jump back and forth between. I will try my best to keep it as linear as possible, but for those times and failures when it seems we've gotten lost in the forest and the ideas given seem scattered, I apologize in advance.