Heroes, Villains and In-BeTweeners PT. 1

How good and evil influence how we view story and narrative

A common trope throughout human history, whether it’s presented in the form of a narrative, philosophical discourse, discussions of morality, national or international poltics, one’s own ideological foundations, or the basis of how we create civilized societies, there is this idea of light versus dark.

God versus Satan, yin and yang, black and white, a good and a bad.

Opposites and complements.

Even the very fabric that holds together human existence, an idea particularly heavy in Western Civilization, starts and ends with the never-ending battle of good and evil. Philosophical ideas of duality have been explored by everyone from Plato to Descartes and are more or less the entire basis of the Daoist religion and philosophy, which, in a very simplified version, is based on the idea that nature, language, and existence stem from dualistic principles.

That light cannot exist without the dark.

Beauty cannot be beauty without the existence of something ugly.

There is no sadness without happiness.

You can only have being because of non-being.

Basically, everything is one half of the same coin.

Daoism’s dualistic nature is less about ‘this being better than that’ or ‘one must overcome the other’ but, rather, things cannot exist with an opposite.

They are complements to the other, as opposites are harmonious rather than at odds. Their existence is only because of the other.

Religion and Human Evolution

Now, in terms of good versus evil, duality is thee crux of the Judeo-Christian religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, whose cosmological basis is influenced by the idea of an eternal dualistic struggle, and has been infused as the core thread of Western Culture’s metaphorical sweater.

However, the nature of good versus evil doesn’t start with these big three.

Rather, looking back even further, you can explore this theological and philosophical idea having its roots in Zoroastrianism, a theology that ultimately influenced the Judeo-Christian religions and shaped what they are today.

Our identity in the West, the most prominent example particularly in the United States, rests upon the idea that things are either good or bad and that good must always overcome the bad.

It’s something that has been influencing our stories and entertainment since, well, basically, the time we could draw paintings on cave walls. However, it’s taken a more nuanced, philosophical, and ideological shape as we’ve developed over time.

Our ‘hero worship’ or our need to see ‘good’ beat ‘evil’ is ingrained in our DNA.

We have an evolutionary predisposition to morality because it minimizes chaos and danger, the ‘bad stuff’ within our tribes or society. In particular, our Western culture is even more prone to recognizing and attaching to the good versus evil trope because of our culture's history and ties to Judeo-Christian cosmology.

This is not, however, the case in Eastern entertainment or even Eastern thought.

One of the most famous pieces of literature from China, Journey to the West, is a superb example of this difference, and Japanese manga is ripe with morally ambiguous characters, some of which we’ll explore later.

The Bhagavad Gita’s message professes that our “purpose as humans is to discover who we are and kill our demons while fulfilling our calling. Although challenging, this experience can lead to the highest form of self-actualization and thus bring us peace and joy.”

Not quite the same as ‘original sin’ and the promise of Christ as an ultimate redeemer and vanquisher of evil.

Good overcoming evil doesn’t hold the same kind of centerpiece of Eastern literature and seems way more character-driven in that sense than our own.

In Western entertainment, it’s almost second nature to deconstruct and just accept this idea of ‘good character versus bad character’ and ‘good guy overcoming bad guy’ in the stories we consume.

How often do you find in media discourse a review or critique pertaining to someone flawed, making morally incorrect choices, or something being problematic? Over the flaws of a character being the driver.

Instead, the focus is on the messaging and morality, rather than the individual as the needle mover. But is it necessarily something that is true or even needed in every story?

Are the good guys always actually good?

Is our villain actually bad?

Is this character really motivated by evil intentions?

Is the person we’re rooting for maintaining good moral choices throughout their story?

Could a narrative where it’s evil fighting against evil be enjoyable, or do we always need dualism to create the struggle needed in order to create compelling stories?

Throughout this short series, I will be breaking down the good versus evil trope and why a story’s protagonist(s) don’t always have to fall on one moral spectrum or the other, and why heroes aren’t always necessarily heroes, even if we love them as characters.

As well as why it’s possible to not always have a need for dualistic principles clashing to create an enjoyable and consumable piece of entertainment.

Exploring The Various Tropes of Good v. Evil

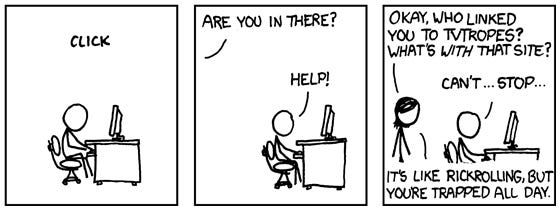

TV Tropes lays out the foundations for the different ideas of this ‘good and evil’ trope in a story.

There are several types, including Balance Between Good and Evil, Good Needs Evil, and even Black and White Morality. So even the structure of Good v. Evil isn’t black and white within the trope itself and, in the spirit of Deconstruction, can be broken down further.

So, what does Good v. Evil really entail in a story?

Well, following the foundations of TV Tropes, which has already done the work for us, here are the general rules for a story.

The following is right from TV Tropes:

Balance Between Good and Evil:

“Good and Evil have rules they must follow. These rules are usually towards overall self-preservation; no one side is allowed to "win" too much. The Big Good and Big Bad restrict their fighting to a Cosmic Chess Game rather than going at it in person, The Hero saves the Villain, and the villain invites the hero to dinner instead of death. If the balance is not maintained, very bad things will happen. What these things are varies depending on the story.

Good winning includes: the universe becoming boring, society stagnating or collapsing from within in the absence of something to struggle against or giving people a chance to show real nobility and virtue by risking their lives to defend each other. Other times, it's enforced by depicting ultimate good as repressive (often Lawful Stupid), or by declaring concepts such as free will or ambition as evil. In other words "too much of a good thing".

Evil winning includes: the universe becoming boring, society tearing itself apart because it's made of Always Chaotic Evil creatures, The Heartless have nothing left to feed on, or Apocalypse Wow.

Good may be portrayed as being intrinsically weaker than the "unbalancing" forces of Evil, implying that maintaining the Balance is the best outcome it can hope for. Another case is that the force of Evil is an Omnicidal Maniac and wants to destroy the balance for that reason, but even then the trope may still be played straight by the force of Evil destroying both good and evil entirely, and thus forming a balance of zero.”

“Evil brings out the best in people. Yes, you read that right. Without true evil to fight, Superman would spend his life getting cats out of trees.

While not a strictly "bad/evil" worldview, it is especially common to villains. Yeah, their job is thankless and unpopular - but they press on, casting the shadows by which the path of truth is shaped.”

“Good versus Evil. White hat versus black hat. The shining knight of destiny with flowing cape versus the mustache-twirling, card-carrying force of pure malevolence. The most basic form of fictional morality, Black And White Morality deals with the battle between pure good and absolute evil.

This can come in a variety of forms:

Motivation: The villains never have a sympathetic motivation for their actions. There aren't any Well-Intentioned Extremists, and The Mole will show his true colors once he's unmasked. Rather, their intentions are entirely for the sake of Evil (and may involve taking over or destroying the world). Likewise, the forces of good never have any evil, ulterior motives for their deeds, as they do good because it's The Right Thing To Do.

Choices: All major choices that the heroes are faced with are either unambiguously right or wrong. There are no real grey areas at all, and when a Sadistic Choice is presented, there's always a third option. Furthermore, the heroes will always make the right choice, unless they're about to learn An Aesop or pull a Face–Heel Turn.

Characterization: The good guys are good, and the bad guys are bad. If there are any morally ambiguous or grey characters around (such as an Anti-Hero or Worthy Opponent), they will eventually shift firmly to one side or the other. They'll either switch to the side that matches their actual perceived alignment, or turn fully good or fully evil. Minor characters may maintain some degree of neutrality, but the major characters will all be on one side or the other. Occasionally there will be a short scene explaining the neutrality is inherently evil (or, very rarely, good). To avoid an Author Tract, some writers prefer to claim that being neutral is similar to supporting the stronger side. However, as the Neutral Neutral page on this Wiki will show, the reasons for being neutral number in the double digits, not including Lawful Neutral and Chaotic Neutral, or any combination thereof.

Stories using this trope usually have a Hero Protagonist and a Villain Antagonist, though this is not always the case. They're also where you're most likely to find Beauty Equals Goodness, although there are stories with black and white morality where appearance doesn't reflect morality.

While it shows up in stories of all kinds, Black And White Morality seems to occur frequently in media marketed for kids. Many stories that use Black And White Morality tend to lean towards the idealistic end of the Sliding Scale of Idealism vs. Cynicism, but this doesn't necessarily have to be the case - in a more cynical Crapsack World, there is more black than white, but the white can at least take a sour form. Works that use both Adaptational Villainy and Adaptational Heroism, or Historical Villain Upgrade and Historical Hero Upgrade for different characters are also deliberately employing this trope to make the moral conflict simpler. Of course, usage of Black and White morality in stories won't always end up sparkling white: this moral alignment is often associated with clichéd writing and propaganda.

Of course, the prevalence of this moral system may lead to the belief that Good Is Boring. Thus, the aforementioned grey spots in a setting like this are a common Ensemble Darkhorse. Badass Decay occurs when the dark horse is whitewashed to conform to the prevailing system.”

The Foundation Has Been Laid

Now, with all of the needed groundwork laid out, how does duality affect a story and really our understanding of that narrative?

Well, for one, you need to decide the’ role of dualities in existence before you can really answer that.

Is it the Judeo-Christian, Zoroastrian idea of conflict that one must overcome the other, or does duality fall more towards the Chinese influence of Daoism, where they are inherently mutually supportive and necessary?

“At the very roots of Chinese thinking and feeling there lies the principle of polarity, which is not to be confused with the ideas of opposition or conflict. In the metaphors of other cultures, light is at war with darkness, life with death, good with evil, and the positive with the negative, and thus an idealism to cultivate the former and be rid of the latter flourishes throughout much of the world….People who have been brought up in the aura of Christian and Hebrew aspirations find this frustrating, because it seems to deny any possibility of progress, an ideal which flows from their linear (as distinct from cyclic) view of time and history. Indeed, the whole enterprise of Western technology is “to make the world a better place” – to have pleasure without pain, wealth without poverty, and health without sickness….The yang and the yin are principles, not men and women, so that there can be no true relationship between the affectedly tough male and the affectedly flimsy female. The key to the relationship between yang and yin is called hsiang sheng, mutual arising or inseparability. As Lao-tzu puts it:

When everyone knows beauty as beautiful,

there is already ugliness;

When everyone knows good as goodness,

there is already evil.

“To be” and “not to be” arise mutually;

Difficult and easy are mutually realized;

Long and short are mutually contrasted;

High and low are mutually posited;

Before and after are in mutual sequence.

They are thus like the different, but inseparable, sides of a coin, the poles of a magnet, or pulse and interval in any vibration. There is never the ultimate possibility that either one will win over the other, for they are more like lovers wrestling than enemies fighting...Thus the yin-yang principle is that the somethings and the nothings, the ons and the offs, the solids and the spaces, as well as the wakings and the sleepings and the alterations of existing and not existing, are mutually necessary.

Yang and yin are in some ways parallel to the (later) Buddhist view of form and emptiness, of which the Heart Sutra says, “That which is form is just that which is emptiness and that which is emptiness is just that which is form.” The yin-yang principle is not, therefore, what we would ordinarily call a dualism, but rather an explicit duality expressing an implicit unity.” -Alan Watts, Excerpts from the Dao De Ching/Lao Tzu

Delving further into how Eastern thought deviates from conflict is the “The Story of The Chinese Farmer,” another Alan Watts example (because he’s such an easy gateway drug to Eastern thought):

“Once upon a time there was a Chinese farmer, whose horse ran away. And all the neighbors came around to commensurate that evening, “So sorry to hear your horse has ran away. That’s too bad.” And he said, “Maybe.”

The next day the horse came back, bringing seven wild horses with it, and everybody came around in the evening and said, “Oh, isn’t that lucky. What a great turn of events. You’ve now got eight horses.” And he said, “Maybe.”

The next day his son tried to break one of these horses and ride it and was thrown and broke his leg. And they all said, “Oh, dear that’s too bad.” And he said, “Maybe.”

The following day the conscription officers came around to recruit to force people into the army and they rejected his son, because he had a broken leg. And all the people came around and said, “Isn’t that great.” And he said, “Maybe.”

You see that is the attitude of not thinking of things in terms of gain or loss, advantage or disadvantage, because you don’t really know. The fact that you might get a letter from a solicitor, I mean from a law office tomorrow, saying that some distant relative of yours has left you a million dollars, it might be something you would feel very, very happy about, but the disasters that it could lead to are unbelievable. Internal Revenue – to mention only one part of that.

So you never really know whether something is fortune or misfortune.”

In “The Story of the Chinese Farmer,” you are presented with a story of conflict at every turn.

Yet, this conflict is never seen as a conflict and, instead, just ‘happenings’ or a flow of events which the character interacts with and isn’t fighting against.

This parable focuses on how the farmer reacts to each situation rather than on his needing to overcome any of the particular situations.

It’s a similar style to how South Park is written, according to Trey Stone and Matt Parker:

“We found out this really simple rule… We can take these beats… of your outline and if the words ‘and then’ belong between those beats, you’re fucked. You’ve got something pretty boring. What should happen between every beat you’ve written down is the word ‘therefore’ or ‘but.’”

This last bit is a really nice way of thinking about transitions from scene to scene as well as establishing a narrative flow. “Therefore” suggests that what happens in the next scene logically and naturally flows from the present scene. “But” suggests that what happens in the next scene is not only logical and natural, but also a complication, roadblock or reversal. It gets at the flow of narrative where some things work out for the Protagonist, other things don’t, but there’s always this push forward into the next scene.

Parker and Stone’s philosophy is character-based (they also happen to be Alan Watts fans too). The ‘but’ or ‘therefore’ implies the character has to make choices based on their makeup.

Narcissists, villains, introverts, cowards, whatever, will make choices that are unique to them. And even within that ‘personality’ bubble, their traumas, past experiences, and new experiences all come into play.

It’s not well, this is the good action to take or the right one, or the villain has to make the wrong one, it’s who is this person and how do they make choices? What will motivate them to interact with this event?

Which circles back to our viewpoint in the world and the schools of thought you would prescribe to: the linear, Western, or the circular, Eastern.

What school of thought you personally prescribe to, ultimately doesn’t matter, but it does determine the influence of how the story works and plays out regarding conflict.

Is the story linear or is it cyclical?

If you subscribe to the Western School of thought, where the story runs linear, A to B, the main character must overcome, and Good will defeat Evil.

The most god-tier of these examples is Tolkien, and his Middle-earth Series. There are basically entire undergraduate and graduate courses on Tolkien’s ability to construct the good vs. evil narrative.

Other examples of this are almost every Disney movie ever, the Marvel Cinematic Film formula, the Bible, or other Western religious texts, Independence Day, and most Golden and Silver age comics, to name just a few.

This Western thought really breaks down to perpetuate the idea of a happy ending or completing an ultimate goal. A problem arises, good wins out, and everything and everyone live happily ever after.

Hero's Journey from like middle school, anyone?

Then, if you take the Eastern model, good needs evil, and evil needs good.

The model is no longer linear but cyclical in good and evil. Some great examples are Star Wars, Avatar: The Last Airbender, or really, the comic genre as a whole.

"Captain America... God's righteous man. Pretending you could live without a war." Ultron to Captain America, Avengers: Age of Ultron

“So long as there is The Sentry, so too must there be the Void.”-TV Tropes, Good Needs Evil

The most common example of this cyclical nature of Good v. Evil and probably everyone’s favorite, is Batman and the Joker.

But that’s for next time.

See you in Part 2.